Female hair loss not so rare

By Jessica Yadegaran

CONTRA COSTA TIMES

Cheryl Brewster was the envy of every gym rat, with her hard body and shoulder-length, sun-kissed locks.

So when her hair began falling out two years ago, the personal trainer was devastated.

“My part was getting wider, I could see more of my scalp and it was no coincidence that clumps of hair were falling out in the shower,” says Brewster, 40, of Orinda.

A slew of vitamins and thickening shampoos later, Brewster’s dermatologist diagnosed her with female pattern baldness and started her on Rogaine — the drug minoxidil — which initially caused Brewster to shed more hair. It is only recently, after a year of use, that Brewster is seeing regrowth.

“I was horrified,” recalls Brewster, who went on anti-depressants. “I didn’t want to be the trainer with the bald head.”

It’s likely that stress and anemia exacerbated Brewster’s genetic condition. In fact, there are endless triggers for the millions of women who suffer from hair loss — from medications and crash dieting to thyroid problems and autoimmune disorders, says Alexander Lewis, a Walnut Creek dermatologist. Millions more suffer from traction alopecia a hair loss epidemic caused by cornrow braids and other tight hairstyles.

Unlike male pattern baldness, which is triggered by a known hormone, women with the condition often find themselves on a frustrating journey with more dead-ends than answers. Often they become depressed, coping with the loss of their crowning glory in a society that favors full, youthful heads of hair. For that reason, many don’t seek help. But a growing online community is now spreading the word on what works and where to get help.

“Women have camouflaged their hair loss for a long time,” says Alan Bauman, a Florida hair transplant surgeon whose clientele is 40 percent female. “But it is definitely coming out of the closet, thanks to new hair loss treatments.”

Hair loss is perfectly normal. The average woman sheds 50 to 100 hairs daily, experts say. With age, follicles produce less quality hair, particularly after menopause. Regardless, dermatologists see just as many women in their 30s and 40s as post-menopausal women, says Dr. Lewis, a Stanford University adjunct associate professor of dermatology.

Like most dermatologists, he performs scalp biopsies and blood tests to rule out medical conditions and usually follows with Rogaine, the only medicine known to slow hair loss. Oftentimes, he prescribes the 5 percent intended for men, not the 2 percent for women.

“There was some increased facial hair with the 5 percent, so they took it down to 2,” he says. “But I haven’t seen a lot of that in my practice.”

Many who take it stop too soon because it can cause flaking and some initial shedding. But doctors urge them not to.

“You have to give it at least four months,” says Kelly Hood, a Lafayette dermatologist.

Cortisone treatments usually follow or are used in conjunction with Rogaine. All treatments work the same way: strengthening follicles to prevent further loss and stimulate new growth.

But when your immune system rejects your hair, strengthening is irrelevant.

Miranda Gardner suffers from alopecia areata, an autoimmune disorder that effects 5 million Americans. The body acts like it’s allergic to the hair, pushing it out in large, circular patches. Gardner, of Concord, first noticed it two years ago, shortly after giving birth to her son.

“I started a new job and this girl kept asking me what was wrong with my head,” Gardner recalls. “She thought I had cancer.”

Gardner recalls feeling “cold breezes back there,” but she couldn’t see anything. That night, she used a hand mirror to look at the back of her head. There, she found a bald spot the size of a golf ball.

“I cried for three days,” Gardner says.

A local dermatologist recommended cortisone scalp injections, which were painful and yielded little results. Next, Gardner saw Vera Price, a UCSF dermatologist specializing in hair disorders. Dr. Price put Gardner on cortisone pills, which she finished in May. She has yet to see significant growth.

“Whoever thinks this isn’t a big deal doesn’t know what it’s like to be 19 and have 65 percent of your hair gone,” says Gardner, now 21.

Today, Gardner’s hair covers three softball-sized bald spots. She spends her mornings fanning it out and hair-spraying it down before tying it in a bun. Most of the time she feels hopeless and depressed, she says, and fears even visiting the salon for a trim.

“I told my mom the other day that I don’t know what I’ll do if I lose any more hair,” Gardner says.

Quality, human-hair wigs cost thousands and, like most remedies, aren’t covered by insurance. Despite the debilitating psychological effects of alopecia areata, it is considered a cosmetic issue.

Unfortunately, even hair transplantation surgery is not an option for those with active alopecia areata, because, post-transplant, the body still sees the hair as foreign, and ejects it.

But for women with thinning hair and about $5,000, surgery can yield significant results.

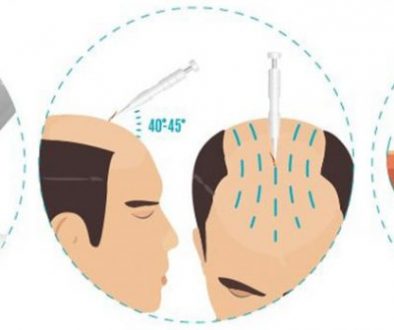

“Ten years ago, the grafting was not microscopic enough for women,” Dr. Bauman says. “Today, the technology is such that we can graft between follicles.”

In other words, the pluggy look is a thing of the past. Surgeons transplant hair from the lower back of the head to the front and crown. Sessions typically run $4,000-$7,000 and most women need one or two sessions, says Dr. Lewis, who also performs transplant surgeries. In the past decade, his female clientele has grown from 1 in 25 to 25 percent of his practice.

Some surgeons, including Dr. Bauman, also perform a series of light-based, low laser treatments on patients, which is said to hit metabolic centers of the hair and, through a photochemical reaction, create better-quality hair.

“I see it as a nonchemical minoxidil,” he says.

But, Bauman says, this treatment is best for women who are just starting to thin. He encourages anyone interested in transplantation to research a surgeon’s background. A good source is the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery at www.ishrs.org.

As with any disease, there are varying degrees of alopecia. Marty Monroe lives with the most severe kind.

The South San Francisco mother of three has alopecia universalis, a rare form of alopecia areata that causes hair loss on the entire body. She was diagnosed with alopecia areata at the age of 8, and by 18, it had advanced to universalis.

“This is the whole enchilada,” says Monroe, who is now 51 and says that humor is what carries her through. “No nose hairs. No underarm hairs.”

When she was little, Monroe’s mother told her it fell out because of nerves. “That’s what they said back then,” she says.

And even though Monroe has traced the autoimmune disorder to her mother’s side, she does believe trauma plays a critical role in hair loss.

For 17 years, she has led a Bay Area support group for alopecia areata sufferers. Sure enough, most of the people she’s met connect their hair loss to a time of severe stress. The death of a loved one. A major life transition.

She gives them all the same piece of advice: “Fake is fabulous. Get a good hairpiece.” Hers is long and brown and wavy.

“I’m really happy with what I have,” she says. “I’ll never go gray.”

Technorati Tags: thickening shampoos, female pattern baldness, Rogaine, minoxidil, traction alopecia, hair loss epidemic, Alan Bauman, Florida hair transplant surgeon, hair loss treatments, Rogaine, alopecia areata, bald spot, hair transplantation surgery, transplant hair